The emerging paradigm of autoregressive VLMs

When the “foundation models” paper first used the term “paradigm shift” in 2021, I remember chuckling at how self-important the term seemed. Today in the end 2024, I am feeling the full gravity of the shift from building problem-specific custom solutions to building upon a common core component that can scale. I think this change deserves to be called a “paradigm shift”, true to Kuhn’s original intent for the term in 1962. This shift is enabled by the emergence of unified task interfaces and the convergence of model architecture. As a result, a framework of execution is also starting to consolidate, with a focus on data acquisition and systematic upscaling. I discuss each aspect in order.

The unifying task interface of autoregressive generation

The early versions of modern, large-scale VLMs are trained contrastively (CLIP), perhaps because image-text pairs are the easiest type of supervision that we can obtain at scale. Soon we realized that making image and text features similar is not sufficient. With a similarity comparison we can only do retrieval and classification, but we dream of something more – features from another modality that is not only similar but also usable – to reason, to generate, to answer questions. These tasks can all be unified under the autoregressive generation framework – and thus, trained on the same language modeling loss. Earlier models like CoCa, BLIP2, X-VLM use a hybrid of contrastive and language modeling objectives. The common benchmarks (VQAV2, NLVR2) are old, yet the unification of tasks is new. Later models (Flamingo, PALI family, BEiT3, Llava etc.) discard the contrastive component and fully use the language modeling objective. While one might argue that putting language-centric tasks into an autoregressive framework is nothing surprising, we also see an increased coverage of more vision-centric tasks.

From the early exploration of DALLE-1, several lines of work (Parti – perhaps Gemini, Chameleon family) also formulate image generation as an autoregressive task under the same interface. Although diffusion is still the leading solution in many settings, it is not as unified with all the other tasks, and people seem to be still pushing on autoregressive generation.

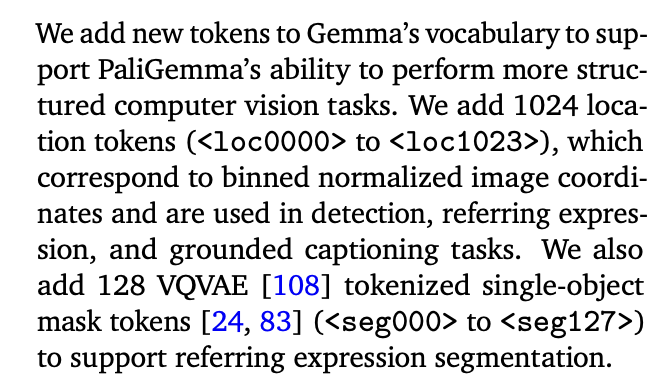

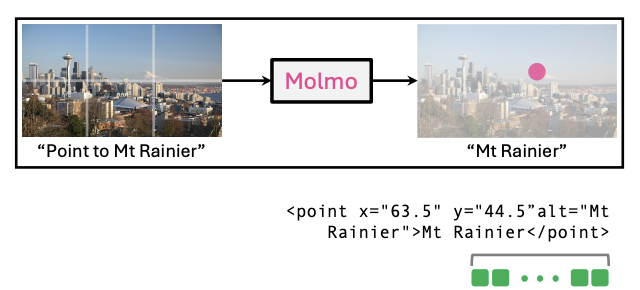

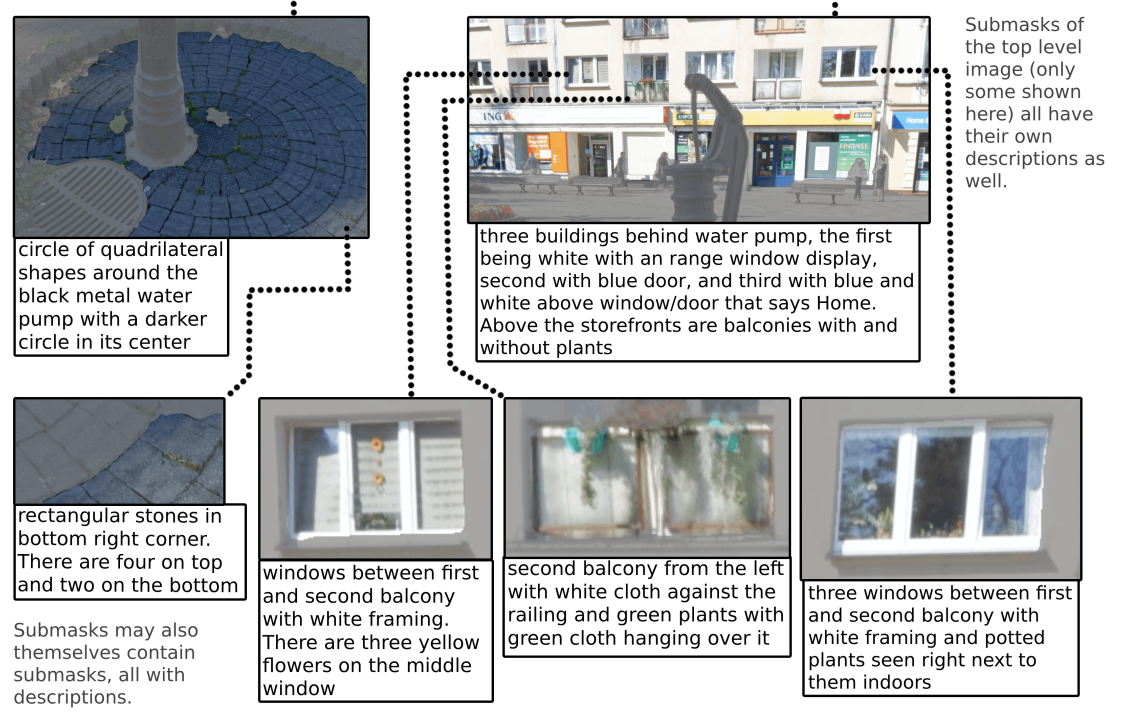

Denser vision tasks are first formulated as more fine-grained language tasks, such as ARO, VL-Checklist and Winoground. Such tasks seem more as an evaluation (or a highlight of current failure modes) and not training tasks. However, more recently, classical dense vision tasks like detection and segmentation are also formulated autoregressively with additional tokens denoting boxes and masks. These tasks are incorporated into pre-training for models like the PALI family, yielding decent performance and enabling considerable improvement on a variety of tasks. Cambrian1 repurposed most vision tasks into a language framework, including detection, segmentation, and depth (formulated as comparison). Formulating dense vision tasks autoregressively (especially the segmentation masks which first start with polygon coordinates then use the VQ-VAE encoding) is mind-blowing for me, yet the performance seems okay. More recently, Molmo releases a “pointing” feature where a VLM can answer a question by “pointing” in an image.

A unified interface is in no ways prescriptive of all future models. However, it proposes one way to push ahead on scale, and one way to let the “divide, iterate, conquer” kick off. For example, Cambrian1 uses a common pipeline to measure the effectiveness of various types of visual encoders. While the comparison certainly comes with its bias, I think this type of interface abstraction is the right way for a large team to make progress on a large foundation model.

The architecture convergence

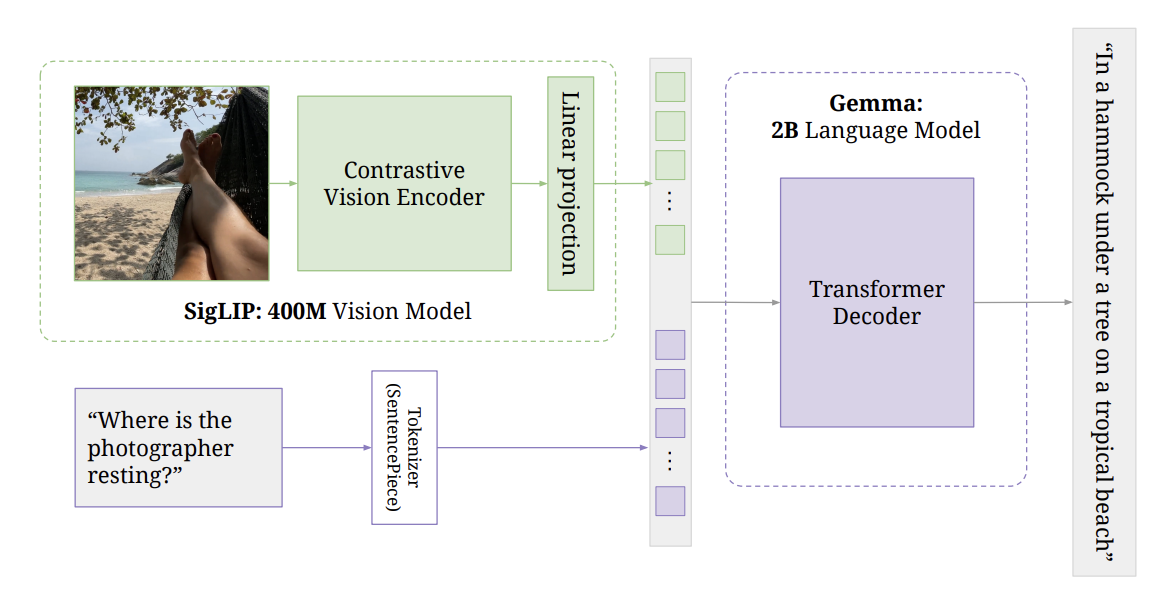

Architecture co-develops with the tasks. It is hard to say which causes which - the unification of tasks under the autoregressive framework, or the scalability of the decoder architecture. Since the output eventually is tokens (language, image or special tokens), the question becomes how to map raw image input to the token space. A few attempts have been cross-attention (Flamingo), adapter with learnable queries (Flamingo, BLIP-2 QFormer), or simple projection (PaliGemma). For the early-fusion models (Parti, Chameleon family), the visual signal is tokenized via some self-supervised discrete tokenizer such as VQ-VAE or Set-a-Scene.

A natural decomposition becomes an image encoder, an adapter mechanism (one of the above three) which maps the image into a “soft prompt”, and a language decoder. Earlier works have attempted to train these encoders from scratch (CoCa, X-VLM, BEiT3), yet later works (PALI family, Chameleon, Flava, etc.) mainly leverage existing models as encoders, partly due to the increased size of these models. Somewhat surprisingly, CLIP-type image-text contrastively learned vision encoders seem to work better than vision-only encoders (Cambrian1), even on vision-centric tasks.

The question on architecture, under the autoregressive framework’s emerging interfaces, now becomes “how to encode and tokenize image”. This is a much more constrained design space, yet one that allows for relatively smooth interface with all the existing language architecture and the tasks that have been subsumed under this framework. Any new model proposal can be easily plugged in and swapped out.

Data

As the architectures are converging, attention has been turning to data and pretraining task mixture. To improve performance in specific domains like OCR or dense visual tasks like detection and segmentatino, such tasks are sometimes directly added into the pretraining mix. While re-mixing existing data is a quick fix, we really do need to think hard about what new kinds of data can enable new capabilities or big improvements.

Throughout the history of AI, data has usually co-developed with the architecture. On the one hand, the availability of supervision at scale greatly determines what models are possible to train. For example, image-text pairs naturally gave rise to contrastive models. Interleaved HTML text (CM3) at scale enables mixed-modality output models. Dense datasets like COCO (and the plethora of datasets built upon it) enable models that have any ability to reason in a denser/object-centric manner. On the other hand, smaller-scale POCs determine what types of data is worth investing on, as one can see in the lines of industrial work that either get scaled up or become discontinued.

One good example of new form of data is PixMo-Points. The point dataset with 2.3M Q&A pairs and 428k images enables Molmo’s new pointing feature. Their data collection via speaking and automatic speech-to-text transcription also greatly improves annotation efficiency. Meta also released a dense, mask-level annotated dataset called DCI this summer, although only at a 7k-image scale. Such a dataset, if scaled up, has the potential of greatly improving grounding.

What kind of mechanistic investigations do we need

With much of the community interested in the common goal of building a good multitask VLM, there is an increasing need of systematic understanding of what might work and what might not. While in old-fashioned ML works there is usually a small section reserved for theoretical derivation that is supposed to serve this purpose, in the current day we need a different kind of mechanistic understanding. The focus should be to guide the investment of time and compute, understand what scales and what does not. Good examples include Idefics2 and Cambrian1, which define and explore the design space and scaling laws, so that not everyone needs to repeat the same experiments before making their own design decisions. While seeing so much emphasis on scaling in research is surprising, this heralds that something is on the horizon and concerted effort is forming within the community.

What’s next?

The forming of one set of interfaces does not mean we already nailed down most of the problems. On the contrary, it formulates one design space which can help guide us in tackling future problems in a more structured way.

- While the autoregressive framework has promise to scale, this does not mean exploration on other fronts e.g. diffusion should stop. Perhaps one could think more along the lines of unification of the two. Especially, diffusion strikes me as a much more natural way to model dense tasks.

- Going sub-object level – the main difference between the image and the language modality, in my opinion, is the rich details that the vision modality embodies. Up to the object level, one can imagine some level of abstraction into a much lower-dimension token space, yet we can perceive sub-object details on different levels of granularity, depending on the context. This is not yet well-formulated either in task or in architecture. The current way of tokenizing might or might not be sufficient.

- What are good ways to encode 3D data (for any representation), and what are good task formulations that can represent the needs for embodied applications well, while remaining compatible to the existing scalable framework?

To these ends, I did my own investigation on generating dense semantic features for 3D point clouds, called Find3D. Segmentation/localization is a straightforward use case. How to leverage this now-acquired dense knowledge to enable better reasoning? How does this representation fit into the broader VLM frameworks? These are questions that remain to be solved.

In a sense, with the interfaces emerging, the line between free research and product roadmaps become more blurred. Coordinated, large-scale efforts are now possible. We are seeing enough initial evidence that if researchers combine efforts and work under compatible interfaces, our collective impacts could add up to something quite exciting!

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: