Rodney Brooks, Tolstoy, and World Models

I first heard of “world models” before I started grad school, when a mentor mentioned Rodney Brooks’ 1991 paper “Intelligence without representation” to me in a casual discussion. Brooks raised the famous idea that “the world is its best model”, arguing against an agent maintaining an internal “world model” and favoring emergent behaviors via interacting with the environment. Fast forward 30+ years to 2025, “world models” have now become a buzzword with the release of models like Genie3 and Marble. Although we now talk about “world models” in a completely different context than Brooks, the fact that we are revisiting a core conceptual idea of AI indicates that we are at a significant transition.

From “What Is” to “What If”

Computer vision started with perceiving: recognition, the detection and segmentation, all aiming to answer the question “what is”. Now that our perception capabilities have become good enough that we can start to ask the question of “what if”: how the environment, or the “world”, will evolve given an agent’s action. Furthermore, this is not in a man-made symbolic abstraction, but in the open world described by visual input - same as what humans see.

This is significant because since Brook’s time, whenever we think about “what if”, or “cause and effect”, our modeling instinct kicks in, and we end up defining a model and choosing a fixed parametrization, only to find out later that it’s not general enough. Furthermore, the more structure there is, the harder to leverage large-scale, naturally-existing data (i.e. videos). If the world is represented as videos, that is general enough. How about actions?

What is Action? From Navigation to Manipulation++

World models started with navigation, and later ones like Genie3, Marble, and Hunyuan-WorldPlay are all heavy on navigation. The action space is thus very constrained. While some world models like RWM and IRASim support manipulation in the context of robotics, the action space is still not fully general. If we want to encompass all actions available from natural videos, the hairy question of “how to define actions” arises. This is a question I raised at the “Embodied World Models for Decision Making” workshop at this year’s NeurIPS. Hands? End effectors? While having application-specific action parametrization (trained on application-specific data) is an easy answer, it seems dissatisfying.

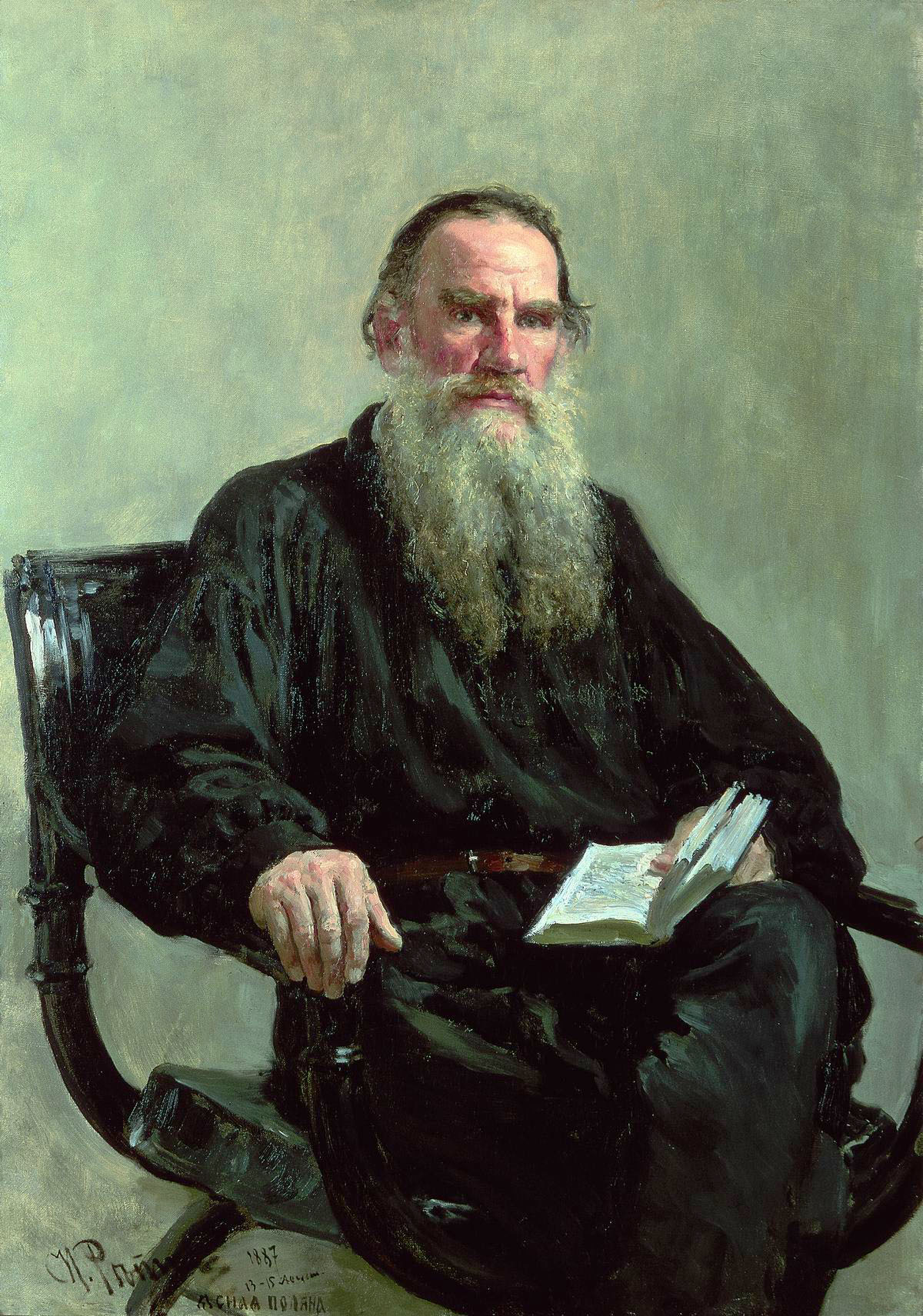

After all, we do have general action data in natural videos. But what is an action? For humans who like to categorize and analyze (rather than just devour data), action and causation are difficult but fascinating topics. Past thinkers like Tolstoy have pondered this.

If I pick up my phone, that is definitely my action. How about the dog running in the background? How about the leaves falling? The first domino falling? The 10th domino falling? A sudden wind? To truly categorize these, there is the concept of “initiation”: someone initiates an action; and “reaction”: the state just evolves according to the laws of physics. This delineation relates to the philosophical question about agency and free will. On the topic of actions and effects, Tolstoy has an interesting and beautiful discussion in War and Peace, via the example of a car’s motion (in analogy to the war’s development):

“Wheels creak on their axles as the cogs engage one another and the revolving pulleys whirr with the rapidity of their movement but a neighbouring wheel is as quiet and motionless as though it were prepared to remain so for a hundred years; but the moment comes when the lever catches it, and obeying the impulse that wheel begins to creak, and joins in the common motion the result and aim of which are beyond its ken.” War and Peace, 1869.

Whereas actions in games are usually abstracted into atomic primitives, actions in the natural world are not atomic nor discrete. Everything exists in a concurrent continuum - it is hard to say what is the beginning of action, what is derived, and what is the end. While we do not need to immediately jump to that level of realism in world modeling, we do need to handle more general actions that occur in real-world videos. In my opinion, the two requirements for action representation are: a) precise. The representation needs to distinguish between a 1mm difference between picking up a glass vs. breaking it). and b) general. The representation needs to encompass different embodiments, concurrent actions, and actions by agents which move in and out of the frame. Hopefully, by choosing a good, general action formulation, we can teach our world models to learn about cause and effect without needing to become philosophers ourselves.

Context and Memory

Having worked on 3D vision, questions about consistency, state, and memory keep me up at night, as you can imagine. One can say that “3D is the memory of object permanence”. And it is true that as humans, we only see 2D in video-like form, and we have some form of non-photogenic memory that allows us to re-enter a room we have visited before, perhaps from a different entrance (and thus a different viewpoint).

The surprising learning from LLMs has been that we don’t need a recurrent architecture for context - full attention to the context (with good retrieval/summarization) is all you need. Long-context techniques such as linear attention have been developing rapidly. However, does this hold true for world models? The key difference between world models and language is that world models encompass a lot more details that might become important later on, and a conceptual understanding of a scene is not enough. For example, if you want to pick up a can that was seen on a table a while back, the exact location matters. Even if we do not rely on context and equip our world models with stateful memory (Hunyuan-WorldPlay has an initial version of this), if the memory is by design compressed and lossy, do we think that is enough?

I expect our world models in 1-2 years to look quite different from what we have today. The initial prototypes are impressive enough that they inspire us to think along this new direction of letting AI model “what if”. This is an extremely difficult task, since our greatest philosophers have spent lifetimes pondering over how to understand “what if” and causations of our world. It is exciting to think that the design decisions today might play a role in eventually shaping how we model the world and automatically train future agents. I am actively thinking about many of the problems mentioned above (and more), so let’s chat if you are thinking about similar problems!

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: